The latest data available from the Office for National Statistics informs us that in 2015 there were a total of 6188 suicides recorded with 75% of those deaths being male, which equates to 16.6 per 100,000 population. While this is still a shocking figure, this is a slight reduction on the 2014 figures where the figure was 16.8 per 100,000 population.

Worryingly, in 2015, female suicide rates reached their highest since 2005 at 5.4 per 100,000 population.

Clearly suicide is a hugely sensitive and complex area and I’d like to make it very clear from the outset that I am in no way clinically qualified to deal with clients who are suicidal, but as a coach that has experience of working with men who are severely depressed, I can understand that in itself, perhaps depression, in itself, isn’t what makes a man suicidal but more the feelings that depression brings with it – hopelessness, lack of worthiness and other similar negative feelings.

In an article for The Good Men Project, Dr. Jed Diamond examines the work of Dr. Thomas Joiner around why men, in particular, succumb to suicide. Dr. Joiner found a number of key areas of interest; namely that feeling suicidal isn’t something that exists within you forever once you feel suicidal, moreover that suicidal intention is transient.

Joiner proposes that there are three key motivational aspects which contribute to suicide. These are: 1) a sense of not belonging, of being alone, 2) a sense of not contributing, of being a burden 3) a capability for suicide, not being afraid to die. All three of these motivations or preconditions must be in place before someone will attempt suicide.

Given my recent experiences, this proposition sounds too simplistic as an offer of why men commit suicide – I feel it to be a far more complex set of circumstances than a required three ingredient formula.

Of course, there are many people on the internet, books and in journals who may feel qualified to offer reasons why – and this is the point. When men and women decide to commit suicide without reason the family will forever be asking the question “why?” – I do it myself sometimes!

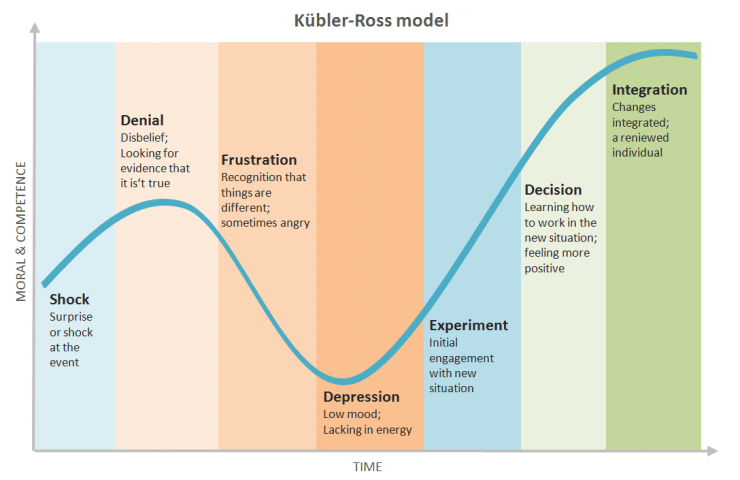

Families and individuals struggle to come to terms when such devastating actions are felt within them or their family. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’ stages of grief accurately define five key stages that may happen as an individual struggles to cope with their loss. This isn’t to say that everyone will experience all stages and some people may stay in a particular stage for longer than others – grief is a very individual process that we must go through in our own time. For me, during the cremation service of my long time friend, and for the first time, I recognised anger as an emotion, which was quite quickly followed by severe loss. Of course, his parents were experiencing all together more extreme emotions of utter loss and emptiness.

I happen to know a director of Crisis who, some time ago now, mentioned to me that in their experience in dealing with suicidal men it only, often, takes two major areas in a man’s life to start derailing for him to feel suicidal. This could be the breakdown of a long term relationship and the loss of a job or perhaps being bullied and being made homeless.

For me, there has been a long-standing connection with social conditioning and male suicide. Again, I’ll reaffirm that I’m not technically qualified to back these statements up – it is more of an observation, but the whole question of men feeling that they have to live up to stereotypical images of “be strong”, “Man Up” and “Men don’t show their emotions” are all interlinked with stress factors, which for some men, are completely and utterly unachievable and so they live every day of their life feeling that somehow they can never live up to expectations.

Numerous other factors have been put forward as the cause of the gender paradox. Part of the gap may be explained by heightened levels of stress that result from traditional gender roles. For example, the death of a spouse and divorce are risk factors for suicide in both genders, but the effect is somewhat mitigated for females.

In the Western world, females are more likely to maintain social and familial connections that they can turn to for support after losing their spouse whereas males typically do not have that strong support network around them and so feel alone in difficult times.

In any event, the message that I want to get across to all men and women reading this is that I’d like for you to seek help from a professional immediately. If you are reading this and potentially feel a loved one may be suffering, please direct them to the contact details below. These people are trained and qualified to help support you in a non-judgemental way and only want the best for you.

Samaritans: 116 123

Mind infoline: 0300 123 3393 (Monday to Friday, 9am to 6pm)

In an emergency situation you can always call 999 or 111 if not an emergency.